The Blueprint #8

This week The Blueprint changes to focus more on analysis and opinions, starting with a new report on the circular economy, and countries attempt to nudge sustainable individual behaviours.

What’s The Blueprint About?

The Blueprint is a biweekly newsletter in which I share 10 links about service design and the planetary crisis. It aims to explore the different service design relevant problems arising from the planetary crisis, and the planetary crisis relevant service design thoughts, processes, tools and solutions we can learn from as a community.

Hello! Over the last 7 publications, I’ve shared links in relation to service design and the planetary crisis. I didn’t expect such a quick uplift in subscriptions, or such good feedback about the usefulness of this newsletter. I’m obviously very pleased with both! However, I also find increasingly difficult to source links, especially that fits into the solution category.

So, I’ve decided to change the formula a bit. It’ll continue to be a newsletter about current events relevant to service design in the light of the planetary crisis but will most likely be a collection of fewer links, with a deeper focus on the contextualisation, analysis and opinions, while trying to keep it under 10 minutes every two weeks.

There will likely be some tune fining over the next publications, please bear with me while doing so. Equally, you’re welcome to reach out to me to provide feedback during the process, by sending an email to hello@sidneydebaque.com.

This will also be the last publication of the year. It’ll be back in January after the holiday season break 👋🏻

The State of Circular Economy

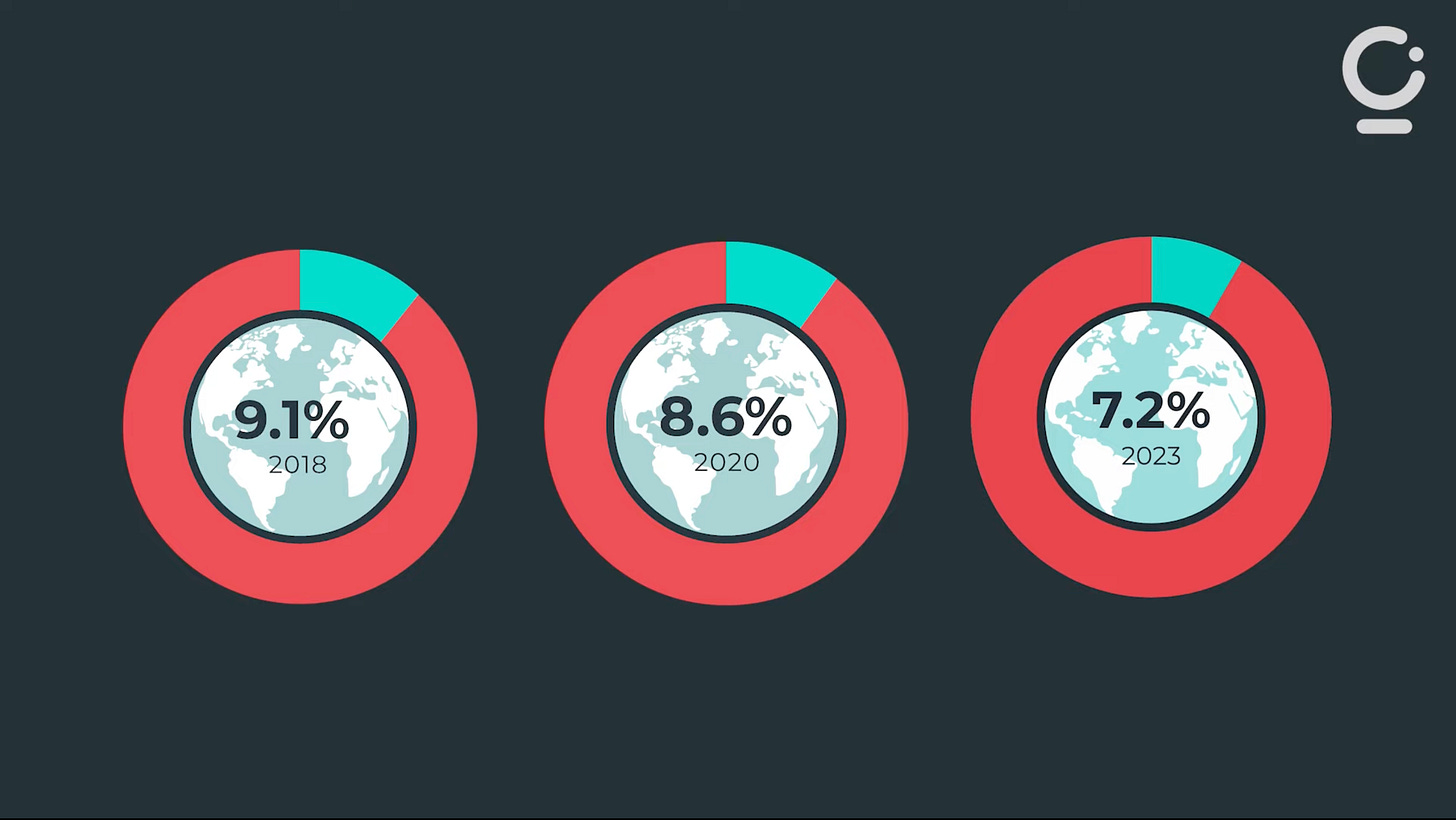

The Circle Economy Foundation has published its 2023 Circularity Gap Report, and the news aren’t good. 7.2% of used material is reused or recycled. This is actually down from 9.1% of reused or recycled material in 2018. The remaining 92.8% materials are either wasted, lost, or trapped in unused capabilities such as machinery or building.

As a result, the weight of materials extracted increases every year. In 1972, 28.6 giga tone (Gt) of resources were extracted, in 2021 the landmark of 100Gt has been crossed. If we’re to follow the current trajectory, by 2060, authors are projecting 190 Gt of virgin material extracted each year.

Adopting a circular economy could reduce our yearly extraction by a third. To do so, authors have identified 4 systems to focus on: Food, Building, Transports and Fashion. Each sector offers leverage to reduce their respective impact, from changing food production model to increasing building efficiency, reduce reliance on cars to increasing machinery lifetime, for example.

From a climate & service design point of view:

The authors also offer 4 systems behaviours to curb our extractivism: using less, using longer, using again, and supporting regenerative practices. The services we design and/or the way we design services have the potential to directly influence the way we use resources.

The decisions we make at the scale of a service inform the way it taps into capabilities. Indeed, the way we set-up a service can reduce the number of delivery trucks we need to operate for instance, by reducing the number of delivery slots available, avoiding express deliveries, using multimodal deliveries to name a few.

But the services we design also offer an opportunity to support people in changing their behaviours regarding the ways themselves use products and resources such as food by creating services to cope with food waste. The main blocker however comes from business models. If we want to foster circular services and behaviours, we need to design business models that do not rely on linearity in the first place, such as membership or pay per usage for instance.

A false good idea: Rewarding individual behaviours with vouchers

Australian, Finnish and Chinese governments are testing schemes to reward people to cut their individual carbon emissions with financial incentives such as shopping vouchers or transportation card reduction. Here, Reuters focuses on China’s example due to the sheer scale of it, and its implementation within a financial market.

Rewarding behaviours isn’t something new: Banks do so with credit scores, insurance company Vitality reduces people’s premium if they exercise or adopt more balanced diets, and at a smaller scale coffee shops do so when people bring a refillable cup. But as reported by Reuters, there might be plan for this individual carbon tracking to be added to the carbon offset market, enabling companies to offset their own emissions thanks to individual reductions.

This obviously poses a series of questions, due to the nature of the scheme itself, as well as its integration into a trading market. Technical, first: how do we account for individual reduction accurately? Are we actually reducing emissions or only recording and rewarding existing behaviours? Can it be beyond carbon emissions? Or are we sure rewarding people with shopping voucher is such a good solution?

But also ethical questions: Should individuals do the heavy lifting to reduce carbon emissions instead of companies? Should it even be a financial asset put on a trading market? If more people sign up to the scheme, would it reduce the cost of carbon credits therefore would companies be more willing to purchase polluting rights? Is this equitable, i.e. do people who actually pollute the most (top wealthy) will care about financial incentives? Or can people be sure that data can’t be used against them?

From a climate & service design point of view:

This isn’t an isolated case as mentioned, as Finland and Australia are trialling similar schemes. UK even commissioned a study back in 2006 to evaluate the feasibility of a similar project. What I do like in this approach is that it tries to balance the lack of accountability towards of the cost of behaviours on the planet into decision making. Indeed, the way the system is currently set-up often rewards negative actions: food grown far away is cheaper, sustainable savings yield a lower interest, mortgages for sustainable projects have a higher rate and lower borrowing cap, to name a few.

However, this is barking at the wrong tree. What seems to be a good idea actually contributes to the issue even more. It commodifies climate action, offload responsibility onto individuals, and will likely have no effect on people who pollutes the most and generate only marginal reductions amongst people who already pollute the least.

This is a good example of what not to do as the service fails to address the wider system it fits in, resulting in being a failed attempt at best, or a disingenuous solution leveraging a financialisation opportunity at worst.

Other noteworthy news:

Almost every home in the UK are subjected to above WHO limits air pollution. [The Guardian]

Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels hit record high in 2023. To stay within the 1.5 global warming objective, we need to achieve net-zero by 2040. [The Guardian]

Portugal ran the whole country only on renewable for 6 days straight, slashing energy costs to almost zero for consumers at the same time. [Canary Media]

AI Is Becoming a Band-Aid over Bad, Broken Tech Industry Design Choices [Scientific American]

Generating an image with AI consumes as much as fully charging a smartphone. [MIT Tech Review]

// That’s all for this edition, will be back in January - feel free to reach out in the mean time if you have feedback about this new formula 👋🏻

I’m a freelance service designer who helps public and private organisations intervene to mitigate the impact of the planetary crisis on humans and vice-versa.

You can contact me about for questions, comments or consulting at hello@sidneydebaque.com